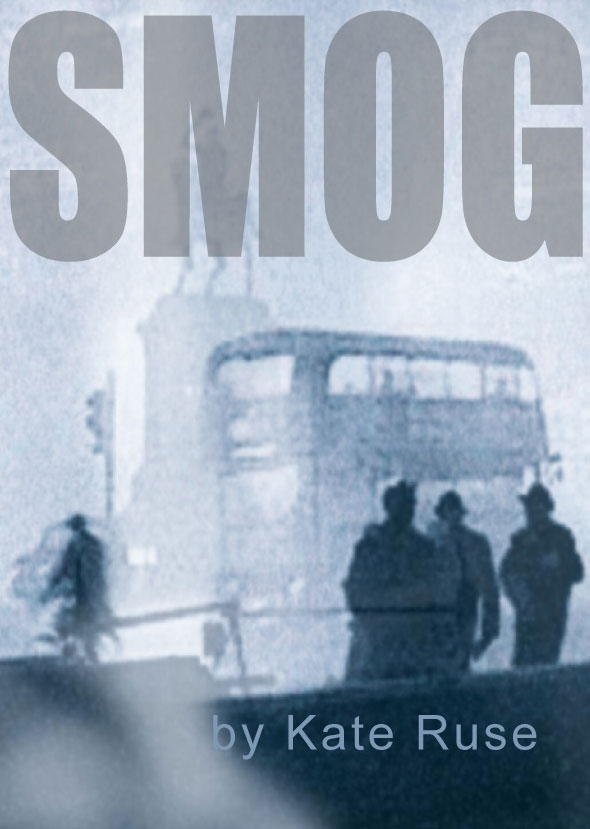

Smog

CHAPTER ONE – LONDON, NOVEMBER 1952

Getting off the bus Charlie stepped into a dense pocket of fog. It had swept around the corner, a nicotine coloured cloud breaking up under his feet. He had sat upstairs on the bus and as they travelled from Chalk Farm to Baker Street he had watched from above the pattern of the fog, at times swirling in clumps then fading and dissolving, leaving an odd grey visibility that stole the features from the faces of the commuters. He pulled up his collar, yanked his hat down, hunched his shoulders and wondered whether he looked like Orson Welles in The Third Man.

The weather was what his mother called ‘bitter’ and Charlie always thought of that as a taste like lemon peel or the stuff they painted on your fingernails if you were a persistent nail biter. He buckled his belt tighter and moved swiftly towards the square. He was looking forward to getting into the office early. He’d put the gas heaters on in the two rooms and make a cup of tea. Then he’d sit down and go through the filing, pasting the coloured strips that Mr. Winters now wanted on all the folders, thereby colour coding the work so that blue was divorce, red missing persons and so on. Once engrossed in this task he knew he would stop thinking. Stop going through all the alternatives, the imaginings, the repercussions. All the things that could perceivably happen when he told her he wanted to leave home.

He had woken early with a nagging headache and that gloomy feeling that he had something awkward he had to take care of. He would just tell her, he thought as he lay savouring the warmth of the blankets and the pillow cushioning his head. He would announce it later when he got back after work. He would simply say he wanted to leave home, get a flat, be independent. He imagined telling her. He knew how she would react. She would look at him with a twisted smile that said ‘yes go ahead’ at the same time as saying ‘you’ll break my heart if you do’. And if he did leave would she slip into depression or would she become more eccentric. Then again maybe she would cope fine, carry on with her life. Did he really need to be there? Maybe he was a hindrance and she’d be glad not to have to do his washing and cook his meals. Wherever he went it wouldn’t be far, he could visit often; even bring the dirty washing back for her, if she really was lost without it.

He almost tripped as he rushed down the street, his eyes watering from the cold, his gloved hands deep in his pockets. He walked down the north side of the square, the fog lifting till it hung like a shroud in the topmost branches of the trees.

***

It was Sally again. She’d phoned once already that morning, her hesitant small voice hardly audible at the end of the line. Charlie knew it before he even picked up the phone. It was a premonition. Both he and his mother were prone to insights of this kind. She would sense his arrival at the front door, seconds before she heard his key in the lock. They would start conversations with each other at the same time, using the same opening words. And once, when he was younger, maybe twelve or thirteen, he had run home from the park, a nameless fear gripping him so tightly that he fell in the street twice before he arrived at the house, to see his mother abject with grief, her face tear-stained and wretched, bending over the sink, a trail of mucus dripping from her nose, hands white as snow. That was when Grandpa Paling had died. A telegram arrived all the way from Penzance, it lay screwed up on the floor for almost a whole day. He and his mother had skirted around it as if it were a bomb that would detonate if disturbed. The stupid person who delivered the telegram had not bothered to stay with her while she opened it. There should be a law, he’d thought, that a person receiving a telegram, when on their own, should have the comfort of a post office official nearby should the news be bad. Although his mother was distraught that the father of her dead husband had passed away, Charlie had felt quite detached for he could only remember meeting the man a couple of times.

‘Hello, Winters and Preston Private Investigators?’

‘It’s me,’ she whispered. ‘Just thought I’d tell you Mrs. Graham’s found Wolfie.’

‘Ah, good,’ he tried to feign relief, make the sort of sounds that would convince her he had been concerned about the dog. There was a brief silence.

‘You said you wanted me to keep you informed.’ There was a defensive tone in her voice.

‘Oh no. I’m pleased Sally, I’m pleased, don’t get me wrong.’

‘Ok. I just thought I’d tell you … you know … you did say.’

‘Yes, yes. I did say Sally. Thanks.’ He could hear her breathing down the line; short little breaths and then he heard her feeding more money into the phone box. ‘No don’t do that Sally. Save your pennies.’

‘But,’ she hesitated and he knew in those few hushed seconds exactly what she looked like in the phone box. He could see her holding her coat tight at the front, as she did. He saw her hand fiddling with the red hair clip and one foot half out of a shoe resting on the other ankle. It was uncanny, he thought. Then her voice broke the silence and dropping to a childish whisper she said, ‘will I see you tonight?’

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Let’s go to the Rose. Meet you there at 7.30.’

He was glad that he was alone in the office when she rang. Both Mr. Winters and Beaky were out. Mr. Winters at a lunch appointment and Beaky on the Hunter case. He liked being on his own. He sometimes sat down at the boss’ desk in his private office, although he always felt a little twinge of guilt. He’d slide his legs straight under the desk, lean back, hands behind his head and then he’d practice a grave yet earnest expression as if he was about to tell a client some very shocking and significant news. But today he had work to do. Sitting at the desk that he shared with Beaky he smoothed down the new folder with his forearm and wrote in capitals on the front the date, 28th November 1952, and then the client’s name SYLVIA BOVEY-CHASE. He underlined it, held it at arm’s length, brought it back down onto the table and wrote over the name again to make it bolder. He looked through the notes that Mr. Winters had made on the first interview. The scrawl was hard to read in places, very much in abbreviated form, jotted down rapidly. He’d look at it later he thought, after lunch.

From the window he could see across and down into the locked garden used exclusively by the residents of the square. A couple of times in the summer he and Beaky had scaled the perimeter railings, hid behind the spread of an aging oak, and removed their shirts to lie almost unseen in the sun. Now every bed and bush and frost encrusted branch was visible. Leaves, left over from a particularly mild autumn, had remained in drifted heaps then decayed and blackened the lawns. No one went there in the winter months. Opposite, on the other side of the square, Charlie could see the rows of hunch-shouldered pigeons, puffed and sleepy on the fanlights above the doors and nestled on the building’s ledges near to the warmth of the eaves. He went to the small box kitchen to get his lunch. What had she made for him today? He opened the paper bag, and lifted up the edge of the sandwich. Cheese and pickle. He thought it might be cheese.

Charlie had intended to wait until Beaky came back before really looking at the new file in depth but as he devoured the sandwich and sipped the cup of tea he had made, he flicked through it again. Beneath a scrap of paper bearing the words ‘client’s brother?’ were three photographs that had been paper clipped together. He separated them and laid them on his desk. The first revealed the smiling face of a young man. The photograph had been black and white but tinted with a weak wash of colour, a splash of pink on the face and hands, streaks of chestnut through the hair. It must have been taken at a wedding or some celebration, for there was a small group of people standing beside him and one could just make out a crowd behind them. Women were in their best, elegant hats and suits. There was a predominance of white. He was sure it was a wedding. He stared hard at the face. It looked as if the person who had taken the photograph had called out the young man’s name suddenly and he had turned, for his body was twisted to the side, and registering the presence of the lens he had flashed a smile that wasn’t quite genuine. It was a rushed smile that didn’t reach his eyes. Maybe the smile of someone who did not like having his photograph taken or did not like the photographer. The young man’s hair was obviously difficult to tame for a lock of it had dislodged from the rest that stood tall on his scalp, and was flopped rather messily over his forehead. This was not an affectation or style choice Charlie was sure. This was how it grew. He flipped the photograph over. Written on the back were just two words, ‘age 18’.

The two other photographs were smaller and one was very creased as if it had been folded for the purpose of concealment. One showed a toddler sitting alone on a park bench, his legs dangling down, and one hand gripping the wooden arm. He was not smiling; in fact he looked as if he were about to cry. ‘Age 3 Market Harborough’, was written on the back. In the last photograph a grinning adolescent wearing school uniform, had been cut out of what was obviously a larger picture. His hair was cut short but Charlie could still see the thickness of it even in its cropped form. ‘Age 14’.

He looked back at the first photograph, held it up off the desk and tried to remember what Mrs. Sylvia Bovey-Chase had looked like when she came to the office. Yes she had dark, thick hair a little unruly just like the man in the picture. She was an attractive woman, for her age, he’d thought. She had draped herself over the chair in Mr. Winters’ office, slowly and with an ease that did not reflect the urgency of a woman with a mission. Below the hemline of her skirt were two neat and finely crafted ankles. And he remembered, as he left the room, dismissed by Mr. Winters, that she had given him a brief but sultry sideways glance, the sort of look that stayed around all day like a spot of blood on a clean white shirt.

***

She was in the kitchen when he got home. The smells of cooking floated down the hallway to greet him. It had been so cold outside the bitterness had burnt his cheeks, made him crouch in on himself as he hurried down the street, head tucked down against the wind. The warm blast of heat from the kitchen and the aroma of cooking meat filled his nostrils. ‘Hello honey bun,’ she said. ‘Hungry?’

She was resourceful his mother. She knew how to stretch the pennies. ‘Two shillings for this pig’s head … he didn’t take a coupon. Should last us the week.’ The butcher had made it unrecognisable, chops, tongue, brain and cheeks all cut and trimmed and parcelled up. It was a roast tonight with cabbage and big chunks of floury potatoes crisped in dripping. The sort of thing you’d have on a Sunday but his mother wasn’t prone to following the culinary conventions of others. They were just as likely to have bread and dripping for an evening meal at the weekends.

‘I’m going down The Rose to meet Sally after dinner.’

‘Oh that’s a shame,’ she said in a rather dreamy manner. ‘I was hoping we could look through that box of books and sort out which ones we want to keep.’ He tried to determine whether she was genuinely disappointed that he was going out. It was often difficult to tell with her. At times she seemed to want him near, sharing her every moment but at others he felt she preferred it when he wasn’t there. She would do odd chores, write letters, darn things, listen to the wireless and sometimes, for he had caught her at it, sing to herself in a rather soulful fashion. He watched her back view at the sink; the knot of her apron was hanging like a tail over her bum.

Suddenly he felt a little sorry for her and he tried to remember whether he had made the announcement of his plans to go out to the pub in a rather frivolous and uncaring way.

‘You can come too if you want,’ he said, even though he was absolutely certain she would decline his offer.

‘No dear. You go ahead. Two’s company.’ She turned to him, her hands full of peelings. ‘Open the bin will you?’

He felt a surge of love for her. It rushed over him like a feral wave on a winter beach. Things had not been easy for her, he knew. She had managed to bring him up single-handed and work at the library full-time but sometimes he wondered if she wasn’t her own worse enemy. She had few true friends, except for Vi, and seemed to keep a distance from activities that might involve her meeting other people. Why didn’t she join the WI, get to know the neighbours better, after all she’d lived there long enough, or socialise with the other women at work. And when she did chose to form relationships or entertain why did she chose someone as sober as Jim Seaton, head librarian, whose wife had died and who hung around his mother, getting his feet under the table every Sunday lunchtime for the last two years.

He and his mother had lived in the house in Pitman Terrace since Grandma Butler died. It was his mother’s inheritance, there was no one else. The women outlived the men in her family. There was a chain of them running like a varicose vein from Great-great grandmother Hicks to his mother. Mother to daughter. There was something very exclusive about it. Preordained and accepted by each generation. He tried to remember how and when the men died but he could only remember tales of Grandpa Butler who sired three children before he was 24 and then died of peritonitis, leaving several layers of matriarchs to collectively rear the little ones. His mother’s two brothers died before their sixteenth birthdays and only she had survived. She clawed herself out of the death trap that had consumed most of the family, for the same scenarios were happening with aunts and uncles from Lands End to John O Grouts. He looked at her now, sleeves rolled up, chopping carrots noisily, her hair in a curled sausage circling her head, the grips sticking out, only just holding the roll in place. She was strong, he told himself, for within this pragmatic, independent woman was all the unused sap belonging to the dead brothers. She was, at the end of the day, a combination of all three of them.

‘Shall I lay the table?’

‘If you want to honey bun.’ She moved aside for him to get to the drawer and he was suddenly acutely aware of his size against her. Had he grown again, since last he thought this very thought? She seemed so small, broad and healthy but little and suddenly she wasn’t strong anymore she was the woman who could not let go of her loss. Losing her father and the brothers had strengthened her but the loss of her own husband Luke, Charlie’s father, had ripped her apart, leaving her fragile and at times dazed and distracted. His death was her Achilles’ heel, a wound that would never mend. Could he leave her on her own? Could he actually move out? The idea of living away from home had appealed to him for a long time. It wasn’t that he didn’t love her he just wanted that liberty, that grown-up separateness. Beaky and he had talked about getting a flat to share in Camden Town. It wasn’t the right time to tell her. Not right now while she looked so susceptible. But he’d have to tell her soon he knew that.

***

Sally was waiting outside when he arrived a few minutes late. She didn’t like going into The Rose on her own, she told him she didn’t like the way men looked at her up and down as if she was some tart who was coming in for custom. He laughed when she said that for she didn’t have the look of a prostitute about her.

It was warm, smoky and full inside, the clanking of a piano sounded muffled from a far corner of the bar. She grabbed his arm and nestled into him, asserting herself as unavailable to the rest of the room but the limpet-like grip irked him, made him want to pull back. ‘Oh, I missed you yesterday,’ she said as he helped her off with her coat and sat her down at a table by the big ornate mirror that took up almost the whole of one wall. He often wondered at that mirror. It was quite something, its length and breadth; the incised border of Victorian frills and flourishes, its tinted amber stain, almost ochre in the shadows. It was the colour of nausea, he always felt. People looked curiously jaundiced in its reflection.

Sally sipped at her gin and tonic and accepted a cigarette that she stubbed out after three drags. ‘Hope you didn’t mind me calling you about Wolfie this afternoon, you did say….’

‘Yes I did say,’ He broke in. ‘Don’t worry about it. I’m glad she found the dog. Where was it?’

‘The bloke down the road, actually the next street along, had taken it in. He hadn’t stolen him. He just saw Wolfie wandering. You know, she lets him out doesn’t she. Silly really.’ She was searching in her bag for something but doing it by feel, not once, he noticed did she look down. He watched her wondering what the hell she kept in there for it was a big clip topped bag with a wide base that always seemed to be bulging. Make-up was what he reckoned she carried around with her. And a brush and comb, perhaps a scarf as well. Maybe ladies stuff too. ‘How’s your mum?’ She asked, still fumbling sightlessly.

‘She’s fine, asked after you she did. Want to pop in and say hello at the weekend?’

‘Oh, that would be nice. I could bring some cakes if you like. I’m going to bake on Saturday, practice run before Julie’s wedding. You know.’ A shudder went through him. The words marriage or wedding made him flinch. He wasn’t ready to start thinking about that kind of thing. Julie was Sally’s older sister, shortly to be married to Jack Judd. She was always harping on about the wedding and being a bridesmaid and how she was really looking forward to her own big day. And she’d look at him with a dewy-eyed expression and he’d smile back, summoning up as much interest as he could before changing the subject. They had only been seeing each other for four months, after all, he thought. Was she expecting him to propose to her or announce an engagement after such a short time? And anyway he wasn’t exactly certain she was the one for him. But he did like her; in fact at the beginning he had genuinely thought he loved her. No other girl he had been out with would let him place his hand right down into the cup of her bra and fondle her breasts. She kissed well too, leaving her mouth open and yielding and he was sure it wouldn’t be long before he could go even further with her. He felt ashamed of these thoughts and knew sex and lust were not a precursor to true love. But he ached for her every so often. Just watching her at times, doing the most simple of things. Laughing with her girlfriends, putting her cardigan on, or rearranging her hair, something like that would get him going and he’d want to lift her off the ground, all 8 and a half stone of her, bury his face into the warm crook of her neck and feel her body compliant underneath him. He loved the smell of her and the softness of her blonde hair and he didn’t care that she peroxided it because it really suited her and was better than the mousey brown she was when he first met her. She encouraged him too. He was sure of that. They’d been to see Humphrey Bogart and Katherine Hepburn in The African Queen a little while back and during a scene of steamy sensuality she had placed her hand on his thigh and given it a little squeeze and he had got an erection and had to fake a coughing fit so that she moved her hand away and he could distract himself with the play-acting.

‘Just popping to the ladies’. She had found what she wanted in her bag but kept it tucked away as she got up to leave. When she returned after what seemed like an age, he noticed her hair had been brushed and restyled and a new layer of lipstick coloured her lips.

***

He knew his mother had gone to bed when he got back. The hall light was on but the rest of the house was in darkness. He tried to be quiet as he manoeuvred around the two floorboards on the stairs, which always creaked especially loudly at night, but he saw the light come on under her door as he passed down the narrow corridor to his room. ‘You all right?’ she called out her voice slurred with tiredness.

‘Fine mum, fine.’ And then as an afterthought, ‘sorry if I woke you.’ He had been all wound up after he dropped Sally back home to Delancy Street but then had cooled down during the long walk back over Primrose Hill. By the time he had reached the top of the mound and surveyed the sweep of London beneath him, a hazy amber light resting over the rooftops, he felt quite elated. In fact there was a moment of exhilaration, a sense of well being and excitement which buoyed him as he started to descend, turning his back on the metropolis and bracing himself against a sudden cold wind. He knew the feeling wouldn’t last. Sally hadn’t talked about marriage again to his relief, being more concerned that he advised her about changing her job. She worked as a filing clerk in an insurance company in Warren Street but was attending an evening class in typing and shorthand. ‘Wouldn’t it be nice,’ she said, ‘if Mr. Winters took on a secretary.’ Her hand had slipped around his arm and she squeezed it tight.

‘Too stingy,’ he said. ‘Likes to do his own typing. But you never know things have heated up a bit lately. We now have four cases on the go at the same time. In fact we’re really busy.’ He regretted saying it the moment it came out of his mouth. He had never mentioned to Sally the truth about his work at the Agency. She imagined, and he hadn’t diverted her from her belief, that he was actively out there hunting down wayward wives, on surveillance to catch fraudsters and spivs or recovering money from debtors. ‘It’s best we don’t discuss it,’ he would say about any job he was on. ‘Sensitive work this is you know. Mr. Winters wouldn’t want me letting things out of the bag.’ She had quite understood and seemed to delight in knowing that there was an enigmatic and confidential side to his work that, although excluding her, also excluded others.

‘Will you put in a word for me if he does decide to…you know…take on a secretary?’

‘You’ll have to pass your courses first.’ The thought of her working in the office along side him filled him with apprehension.

‘Of course. I know that.’ She went sullen for a moment, upset by his lack of enthusiasm. Her hand loosened its grip.

One of the things he found irritating about Sally, he thought as he pulled the covers up and switched off the light, was that she reacted personally to every little thing he said. She took everything so seriously that he felt under pressure all the time. She couldn’t laugh at herself. He had to think carefully before he opened his mouth, weigh up what he was about to say and check out whether any little nuances might offend her. Look how tetchy she’d got over the damn lost dog, when he hadn’t shown enough interest. It made him feel on edge all the time. But they had kissed on the front step of her house, her nose cold against his cheek, the mixed smell of makeup and cigarettes in her hair. It was a brief and fumbled kiss for as their lips touched he thought he heard her father talking in the hall, behind the glass-fronted door.